Ageing in the Diaspora

This blog explores ageing in the diaspora mainly from a personal perspective. However, it could be typical of the many individuals who have relocated from the place of their birth to live in the UK.

General ageing and diasporans in the UK

The World Health Organisation projects that by 2050, the number of people aged 60 and over in the world will have doubled. This change will be reflected within the UK. It has major implications for the structuring and planning of health and social care for this ageing population.

‘The UK is seeing a significant rise in the number of ageing diasporans from the Windrush era (1945-1972)’

Diasporans in the 90’s

Many diasporans now have limited ties with the countries of their birth and have their lives firmly rooted in the UK. Gov.UK – Ethnicity fact and figures identifies that there are approximately 115,550 Black people over the age of 65 living in England and Wales, hence the agenda for managing their health and well-being will require significant attention.

Uniqueness of ageing in the diaspora

The Windrush generation’s sense of belonging as British citizens was recently seriously challenged. Teresa May’s government insulting attacks on some of their rights of residency was clear for all to see. Several people were known to have been unlawfully deported with the event now referred to as the Windrush Scandal. The number of people awaiting the same fate is unknown; an air of uncertainty and anger persists. Beard and co-authors write of healthy ageing being enjoyed by the privileged few and that physical and social environments are key determinants of this.

‘Ageing diasporans are already set on a downward trajectory of unhealthy ageing if social injustice such as the Windrush Scandal, racism and ageism are added to their constant battles’

One of over 14,000 black diasporans now aged 80-84 and having resided in the UK for over 54 years

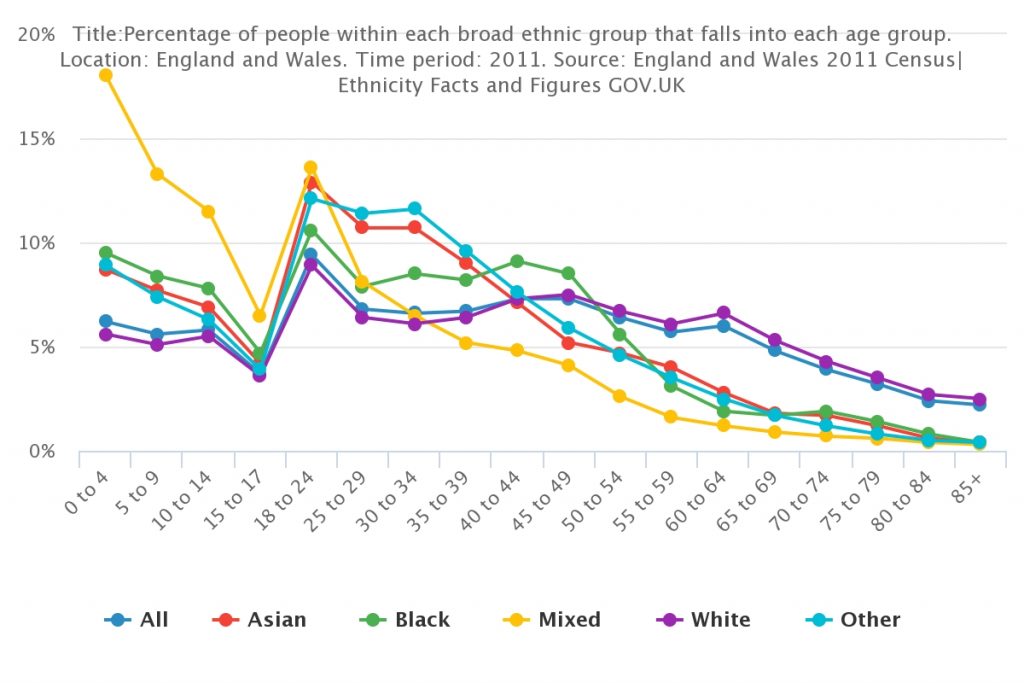

A report by The King’s Fund says that it is expected that individuals 65 and over will have a limiting long-term physical or mental health condition for fifty percent of their remaining life. It is not immediately apparent if these statistics take account of the dislocation caused by migration. It could also be argued that exploring the uniqueness of ageing in the diaspora is needed. Ageing diasporans could be at significant disadvantage in the planning and organisation of relevant health and social care services. Consistent with this thinking is the 2011 census for England and Wales.

‘There is significant decline for Black people over the age of 50 in their survival rates compared to their white counterparts.’

Multimorbidities, hostile environment, and extended pension age

The likelihood of multi-morbidities increases with age, but for diasporans additional contributory factors come into play. Living in a hostile environment fuelled by racism and discrimination affects people in different ways and at different levels. Therefore, exploration and consideration of changes in cultural lifestyles, historical socioeconomic disadvantage need to be addressed. A system geared to facilitating health of indigenous populations can make accessing it difficult for incoming and diverse groups.

Jamaican Independence Celebration in Birmingham

Many Caribbean women ageing in the diaspora migrated to the UK during the 1950s and 1960s and have been caught in the extension of the qualification age for state retirement pension and are having to work for longer.’ The WASPI campaign is showing how women are having to consider a change in their lifestyles and how they might finance their future retirement.

‘ It would seem that a disproportionate number of diasporan women will be affected but the exact figures are unknown.’

Health status of black diasporans and culturally competent care

Diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, obesity and mental ill heath are generally prevalent in the ageing population. However, research such as that of Ian Hambleton and his colleagues suggests that, for diasporans, the effect and negative consequences of these conditions may be significant compared to the effects on their white counterparts.

Implications for delivering and managing culturally appropriate care require practitioners who are themselves culturally competent. The supply of cultural competency training related to caring for ageing diasporans is variable and often lacking.

‘Culturally competent health and social care policy and practice require acknowledging and catering for difference.’

NICE guidelines stipulate the urgent need to develop appropriate evidence-based interventions for African Caribbeans. They experience inferior access to care and suffer significantly worse outcomes in areas such as mental health. Culturally sensitive residential housing and day care such as Nehemiah Housing , the West Bromwich African Caribbean Resource Centre, and the African Caribbean Millennium Centre exist, but similar services and facilities remain relatively scarce.

African Caribbean Millennium Centre

Promoting active ageing

Often with ageing, there is a decline in physical and mental ability but for many people, it is the converse. They are able to improve strength, balance and mobility. The medical community strongly recommends these actions as part of promoting good health and active ageing. However, communicating this message to individuals ageing in the diaspora can be difficult. Many feel they have worked hard all their lives to support their families, often against a hostile system. They believe that they should not be made to work harder but instead, should be looked after.

‘The challenge to change attitudes and behaviours towards healthier ageing should therefore be a goal for us all.’

What diasporans can do to improve their health and well-being

JamaicaMoves, is a campaign which started in Jamaica and recognises the special health challenges faced by its population. Many of the health issues faced by indigenous Jamaicans have followed them abroad and the effects for diasporans, as Ian Hambleton and colleagues have alluded to, may be more significant. Therefore, it is timely to adopt health promotion strategies which encourage, facilitate and target the development of healthy lifestyles of diasporans. Offered at minimal cost or free locally and nationally are park runs, local authority organised swimming and exercise classes, etc. However, they are patchy and reaching and connecting appropriately with diasporan communities remain challenging.

‘Making lifestyle changes generally in later life can be difficult although not impossible.’

‘A rebalance in diet and increasing physical activity are central messages to be delivered in any health and wellness campaign for ageing diasporans, given their predominant morbidities.’

Stroke Association Guidance

What society needs to do to improve the health status of diasporans

The social care within England appears to be becoming significantly under-resourced. This threatens the well-being of the population, especially of older adults. As a part of this older group, many diasporans require special measures which recognises their histories and present context. Their reduced networking, isolation, and loneliness are constant and unwelcome features of this. The majority of ageing diasporans are located in urban cities and Age Concern’s document ‘Ageing and Ethnicity’ implies that this makes them more vulnerable to the vagaries of diminishing resources in the health and social care system.

‘‘Ageing diasporans cite having a sense of home, and religion as important factors in their well being.’

However, paramount in developing well-being is help to build networks nationally and locally. Finding a meaningful place in society and financial security to avoid poverty are also important goals. Targeted and effective dissemination of information about available funds and resources would require comparatively little effort.

Until recently, the plight and unique needs of ageing Caribbean diasporans have received limited attention. Venkatapura identifies that

‘Doing justice to older people requires that we identify the right social response to prevent and correct the direct harm that broader social conditions have done to those people.’

Ageing Caribbean diasporans must be recipients of that social justice.