Golliwogs, Blackface, and Watermelon Smiles

The recent disclosure of England batsman, Alex Hales, blackening his face to attend a New Year’s Eve fancy dress party in 2009, Boris Johnson, British Prime Minister, describing Black people as having ‘watermelon smiles’, and golliwogs being constantly described on social media as favourite childhood toys, are all strong indications of how firmly embedded in British society apparent racism is.

Traditional Hand-Knitted Golliwog Caricature Doll

Apologies and excuses

Hales, in an effort to mitigate his ‘blackening up’, said he was emulating his idol, Tupac Shakur. His admission and apology for being ‘reckless’, ‘foolish’ and ‘disrespectful’ came quickly amid the furore surrounding Azeem Rafique’s calling out of racism in Yorkshire cricket.

Beyond sport, Boris Johnson chose, among several disparaging comments about African people, to describe them by their ‘watermelon smiles’. He insisted that the term was used “in a wholly satirical way” and was taken out of context by reporters, prompting the question: what context could it possibly have been appropriate in?

Hales and Johnson’s use of the golliwog imagery demonstrates how entrenched as ‘a way of life’ racism is. And, were there any doubt about the golliwog and its association with racist imagery, entering ‘golliwog’ in the search engines of common social media platforms, such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram would soon dispel this. Freedom to express racism has found its niche in these easily accessible public spaces.

The golliwog

The golliwog’s existence as an allegedly harmless toy, as opposed to a racist effigy, has been reinforced from the cradle.

Consequently, its development and the racial controversy surrounding it continues.

I first came across golliwogs when I arrived in the UK from Jamaica as a child in 1965. It was at a time when racism was rife and just one month after Malcolm X’s famous visit to Marshall Street, Smethwick. This street also happened to be the back entrance to my secondary school.

The first time, as an eleven-year-old, I was called a ‘wog’, and the deep insult I felt, are still, indelibly, seared in my memory.

This term was commonplace and often seen daubed over walls and posters in my locality.

Golliwogs originated in the Victorian era when minstrels were commonplace. The minstrel provided popular forms of entertainment in the early days of silent film. White actors would paint themselves as comic parodies of how they (white people) thought Black people should look.

The golliwog character with blackened skin, a wide-eyed grin, big lips surrounding shiny white teeth, head covered with woolly hair and attired in multicolored clothes, was destined to become a signatory nursery plaything for many European children.

The Golliwog

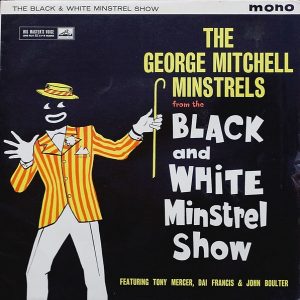

Th Black and White Minstrel Show

The hugely popular Black and White Minstrel Show, which ran on the BBC from 1958 to 1978, ensured that this strong imagery and associations of the golliwog and Black people would become entrenched in British society.

(Photo by George Hooper)

Incredibly, my parents along with many other Black and white families would routinely sit to watch this mimicry.

I often wondered why as a Black family we tuned in to view caricatures that mocked us. Were we just wryly looking on at white performers trying to emulate exceptional Black artistic talent?

The start of racism in the nursery and beyond

Beginning in the nursery with the Florence Upton book, ‘The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls’, followed by Enid Blyton, writers have racialised the discourse and ideology in teaching children about black people.

Childhood dolls (courtesy of Miss Shari)

Over several decades, Enid Blyton’s adoption of golliwogs as loveable mischievous characters in the Noddy books, and the Robinson’s jam golliwog trademark, did little to change or limit the damage and derogatory positioning of society’s attitudes towards Black people. Perhaps, as disturbing has been their influence on how some Black people came to think about themselves.

No place for golliwogs?

Calls to remove golliwogs from stores, confectionary and advertising have generally been heeded. However, whether their manufacture should cease entirely and existing stocks destroyed are still being debated.

Robinson jam ornaments and badges (Leo Reynolds)

Akin to the call for the destruction of statues and monuments linked to slavery, destroying golliwogs will neither destroy the history they represent, nor will it dismantle their contribution to racism.

But, perhaps, confining them to an appropriate corner in a museum might just act as a reminder that the conscious or unconscious bias or racism we are seeing today can often be traced to a very conscious and tangible past.

The National Trust, in recognising that they are ‘displaying objects that are deeply offensive and racist, such as the golliwog’, state they are seeking to ‘better represent[s] diverse childhoods’. The final verdict on whether there remains a place for the golliwogs in the National Trust or elsewhere is still being argued.

Perpetrators of racism who are ‘called out’ when they offensively caricature Black people can neither claim ignorance nor unconscious bias.

The golliwog epitomises a racist past. It should never be presented merely as a nostalgic toy, a figure to mimic, or indeed its features adopted as a source of satirical fun.