Introduction

It is not very often I get animated by the negative rhetoric on social media directed at African Black hair. However, when it is coming from Black people, as disappointingly it often does, I cannot remain passive.

If you perceive Black African hair to be: a symbol of beauty, flexibility, elasticity, an assembly of coils defying the laws of gravity and often presented in a display reflecting centuries pf coiffeuse artistry, then you might understand why I am so energized by comments that seek to degrade my hair type. More critically, I am appalled at the harm and the negative imagery constantly being proffered to our susceptible young people who are already being challenged in establishing confident body images.

Courtesy of Good Faces

The derogatory comments and comparisons that I hear when referring to African Black Hair, in particular to its Western African type, are mind-boggling.

Terms such as “rough-head”, “tough-head”, “hard-head”, “pepper grain” are common, while comparative terms for East African, Indian, or European hair of “smooth”, “silky”, “shiny”, “gentle”, and “soft” are not unusual.

Hair and identity

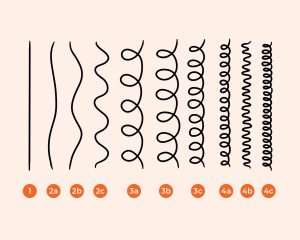

Medical categorization of hair types of from 1 to 4, signifying very straight hair to tight coils, has done little to influence public perception and has created critics of its own definitions.

Courtesy of Holland and Barrett

The value and significance of the hair on our heads, often referred to as a ‘woman’s crowning glory’, should not be underestimated as often it determines how we wish to present in public. Gillian Scott-Ward and co-writers emphasize the significance of hair and its intersection with politics and identity on an individual’s psychological and emotional experience.

It is no coincidence that following the Covid lock down of 2020, one of the longest waiting lists for appointments was for hairdressers and barbers.

From its presence to its loss, in the styles chosen, as an indicator of age and not least, of heritage, hair is a dominant feature of how people are perceived.

Hair and race

A most notable misconceived, racist, and ignorant illustration of the latter was witnessed during the apartheid regime of South Africa, in the ‘pencil test’, where the ability of the coiled hair to stop a pencil falling to the ground was a signature of how ‘coloured’ a person actually was.

My 1970’s afro

So, why are we perpetuating a racist stance that have historically disparaged and traduced the characteristics of West African Black hair?

One might say it is through ignorance, continuing racism, threats to self-esteem, lack of confidence, or for many other reasons. Regardless, I cannot passively stand by and see an important characteristic of my human form, and those of people like me, being continually besmirched. Neither can I ignore some of the recently published research which indicate compounds frequently used to restructure Black hair contains ‘ingredients linked to cancer, reproductive or developmental harm, or endocrine disruption’ and hence, a need for caution.

Personal accountability

Individual responsibility to reflect on the language we adopt, in the signals we send about ourselves, and definitions of self-worth are all part of developing healthy mental attitudes and lifestyles. The overt and covert portrayal of positive body image is dependent on healthy mindsets -which we are reminded are constantly being eroded, particularly by the impact of social media on our young.

We have come a long way in our attempts to stamp out racism, although we still have very far to go.

However, unless we recognise the deep-seated nature of how racism has traduced what we believe to be ‘good’ and ‘bad’ in ourselves, be it related to hair or otherwise, the oppression, negative rhetoric and attitudes directed towards Black people will continue unabated.